I first encountered one of my favorite painters six years ago at the Art Institute in Chicago, a few days after putting my father's ashes in Saginaw Bay. At first, I was relieved to walk among the dignity of marble and skylights, grateful to escape the nervy loop of strip malls and service plazas. But the artwork felt grim, all those little spotlights shining upon the relics of the dead: Etruscan and Byzantine and Aztec, the endless cycle of flourishing wealth followed by rapid decline.

Every image seemed to illustrate our inability to tame our appetites. Drunken feasts and forest bacchanals. Leering portraits of undressed women and four-headed bodhisattvas stomping on the heads of passion. There's no escaping our worst impulses, is there? The abstract artwork in the modern wings tried to sidestep this question with antiseptic sculptures and fields of color that left me cold. So I reversed through the halls, history rewinding as I hunted for the exit until, somewhere between the Renaissance and Impressionism, I hit a wall with three canvases of a crumbling Roman arcade.

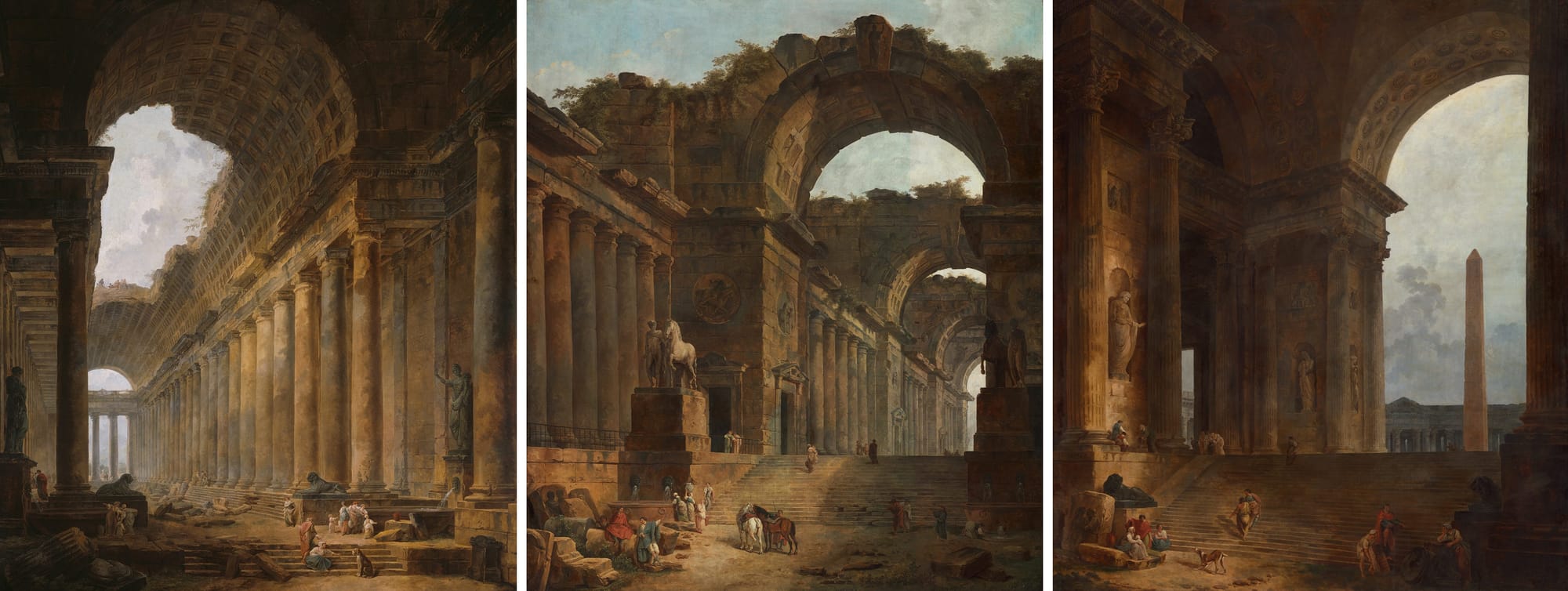

Ruins filled each frame, and I nearly overlooked the tiny figures among the stones, their bodies dwarfed by architecture designed for gods. A woman crouched over a puddle, laughing as she scooped greywater into a pail. An elderly man groped among the rocks with a cane. Young lovers kissed against a statue’s shattered torso. A floppy-eared dog gnawed a bone.

The label next to the paintings offered no information except their titles: The Fountain, The Obelisk, and The Old Temple—dispassionate names that gave them the force of fact. They were painted in 1787 by Hubert Robert. (Such beautiful cadence in that name: Hubert Robert. Say it out loud and you can’t help but smile.) He was known for his capricci, a genre of architectural fantasy that disregards time and scale.

The happy woman with her pail of water, the blind man and flushed lovers, all of them were dwarfed by history, eking out an existence in its shadows. Although the painting was devoted to the relics of a grander age, it also felt like prophecy, a vision of future generations fetching water among the cinderblocks of a discount department store.

My eye kept returning to the dog. Its gums glistened as if on the brink of laughter, and a very different painting came to mind: a watercolor of a grinning clown that hung above my bed when I was small. How I dreaded going to sleep, knowing I would be left alone with that smile when my mother shut the door. Even with the covers pulled over my head, I could feel it above me, laughing in the dark. One night I slipped the clown under my mattress, and although its face was mashed beneath ten inches of cotton batting, I knew it was there, still grinning. So I slipped the painting into a stack of newspapers and buried it in the trash. My parents never noticed.

Thinking about it now, I was not afraid of the clown, only its smile, permanent and unexplained. Most nightmares begin with a smile like that: a favorite doll or jolly grandparent whose grin crosses the thin line between cheer and menace, when happiness exists without reason, something even a child can recognize. Attempting to be joyful without acknowledging the world's sorrow is dishonest. A grin without purpose is insane. Maybe true happiness requires a tragedy to transcend, like the face of the woman with the pail of water. Look how she's laughing: full-bodied and well-earned because she knows her life beneath the obelisk is bizarre; nothing to do but accept it.

This was enough to keep me returning to museums, where I would become increasingly emotional in front of paintings, hungry to connect to some kind of history or tradition, to stitch together a patchwork faith that might arm me against the darkness waiting for me when I returned to my car.