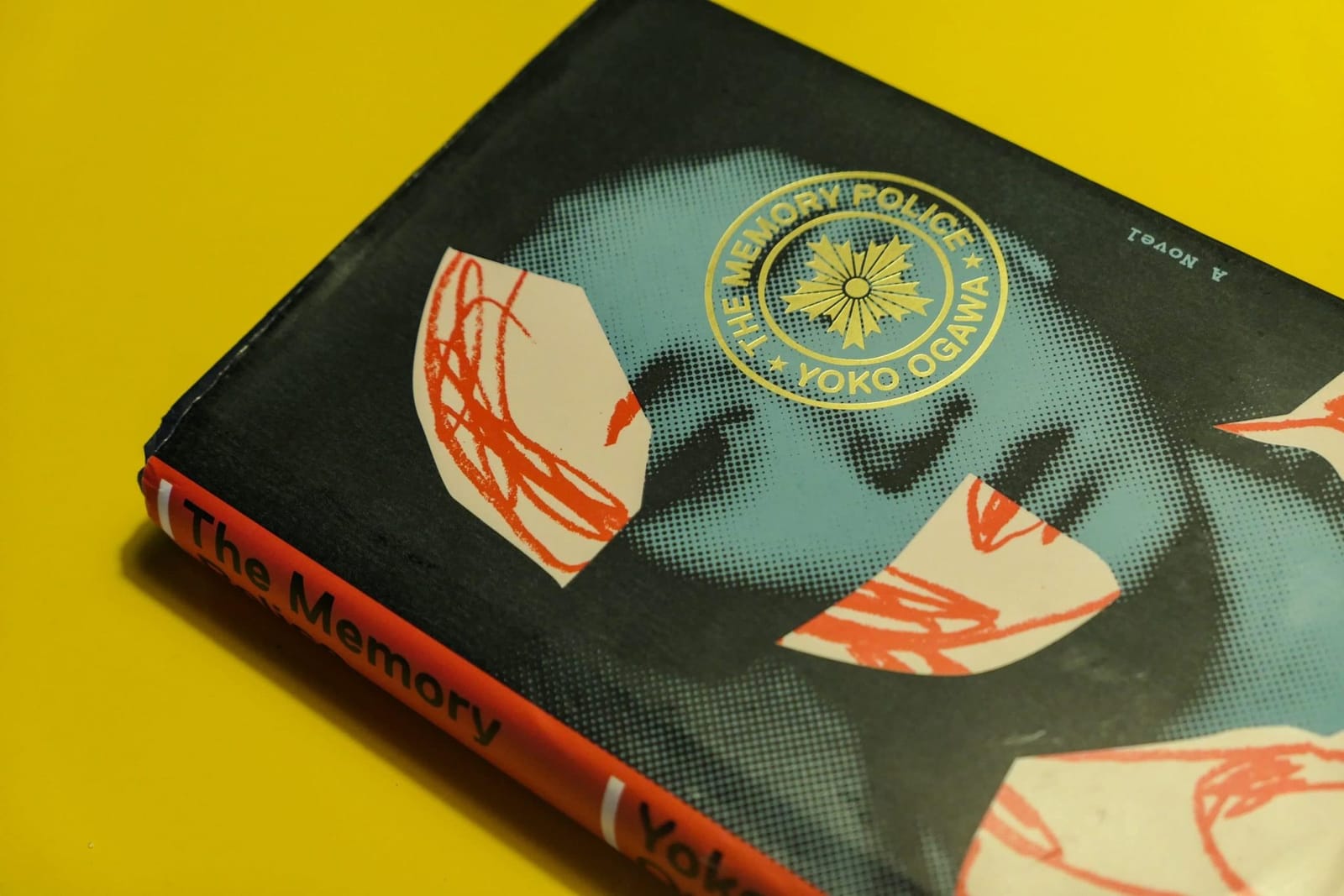

In Yōko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, the residents of an unnamed island suffer the ritual disappearance of objects big and small. Flowers. Lemons. Perfume. Calendars. These erasures are enforced by a surveillance state that deforms the lives of its citizens a little more each day. First published twenty-five years ago, Ogawa’s meditations feel incredibly urgent in today’s atmosphere of digital disorientation and alternate realities:

But in a world turned upside down, things I thought were mine and mine alone can be taken away much more easily than I would have imagined. If my body were cut up in pieces and those pieces mixed with those of other bodies, and then if someone told me, “Find your left eye,” I suppose it would be difficult to do so.

This is a haunted fable with secret rooms and voices trapped in typewriters. Although the surreal metaphors of Kōbō Abe or the eerily arid writing of Albert Camus come to mind, Ogawa’s writing lives in the moments just before a dream evaporates.

Sooner or later, any story about loss becomes a story about normalization, and The Memory Police captures the ways we adjust ourselves to fit the cruel logic of the world, whether it is delivered by the power of the state or the inevitability of death. We can become accustomed to terrible things. What’s the alternative? Ogawa provides an answer through moments of grace and devotion to the truth—and its final pages are devastating. I can’t remember the last time I cried while reading.