A sunny Wednesday morning with highs in the 50s, the sun goes down at 5:30pm, and I’m recovering from Francis Bacon’s animal paintings at the Royal Academy. The introduction on the wall said his paintings speak to “our current predicament”—an elastic phrase that set my mind wandering through today’s calamities and disasters, wondering how they might connect with Bacon’s figures that flicker between human and beast.

We inspected these grisly images on a rainy Tuesday afternoon. Some of us wore masks, others were bare-faced, and all of us were confused about how to behave while the pandemic zigged-and-zagged. Our screens were wallpapered with headlines about new viruses, military incursions, disrupted gas supplies, and economic sanctions. Or as Bacon observed: “The whole horror of life, one thing living off another.”

He described the crucifixion of Christ as “just an act of man’s behavior,” yet his depiction of it looks more alien and magical than anything the Catholics conceived. Bad weather fills Bacon’s canvases: damp and clammy, the faces of his subjects melting in the rain. But it’s more than body horror. There’s reverence for death here. His ghoulish scenes float before me, demanding to be taken seriously. “I think most artists are very aware of their annihilation,” said Bacon. “It follows them around like their shadow.”

What is it about a Bacon painting that yanks me back into the gallery each time I’m about to leave? The mouths. More specifically, the teeth. His detailed grins and snarls provide an entry point into the surreal, for the dissolution of logic into something even more real. My eye struggles to understand the face before me, even though it already makes sense, for it exists deep in the basement beneath words and speech, somewhere among the limbic muck and heat of being a panting, living mess.

Bacon believed in “an area of the nervous system to which the texture of paint communicates more violently than anything else.” I think he’s right.

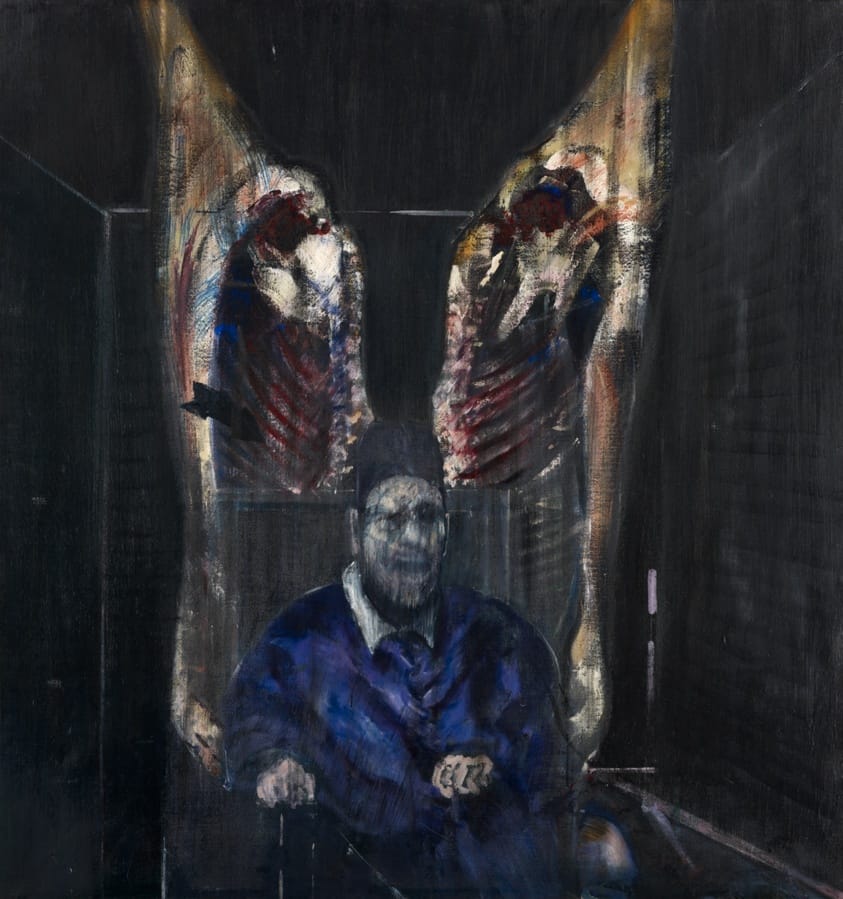

There are many reasons Francis Bacon’s Figure with Meat bothers the mind. It’s a crazed smear of flesh, velvet, and bone, but I think it lingers mostly because the screaming bishop inhabits a zone that cannot be determined, a room etched only by a few ghostly chalk lines. The ambiguity forces us to supply our own nightmares that pulse in the murk just beyond the grasp of language. Which is the whole point of painting, I think. And perhaps horror, too.