I spent the month of February in Iceland as part of the NES Artist Residency, where I worked in a little café by the Arctic sea in the town of Skagaströnd, population 498. There was no snow when I arrived because we’ve ruined the Gulf Stream. Instead, there was an endless twilight that saturated the red rooftops, black rock, and patches of yellow moss. Although I remain committed to black-and-white photography for reasons of simplicity and accuracy, Iceland demands color.

Watching the ships rocking in the harbor, I cultivated elaborate fantasies of trade winds and oil lamps and drowsing beneath a wool blanket while a radio murmured about barometric pressure and shipping lanes. Iceland was an ideal place for imagining other possible lives. Sometimes the clouds and mist hung so low they erased the boundary between land and sky.

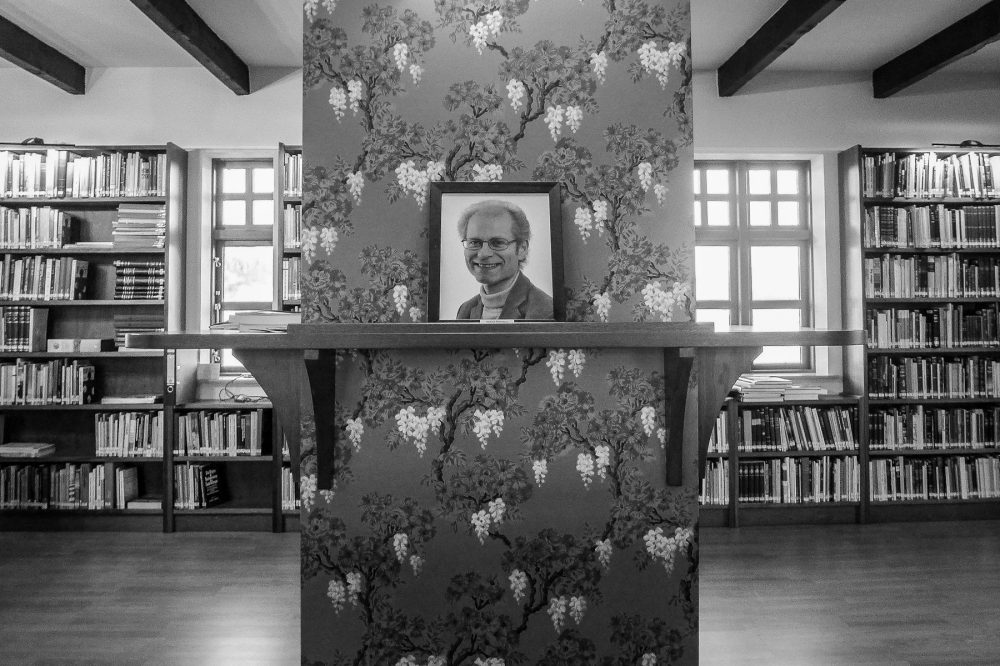

I visited a cozy library lined with books, encyclopedias, and manuals that had been donated by an ambitious collector who passed away in the 1970s. The librarian whistled along with “Manic Monday” while shuffling through papers, a sound that blurred with the wind beating at the windows. And my god, the wind. It knocked us over as we raced along the sea, drilling into our ears and slapping us across the cheeks, sending our voices flying from our mouths. It was a wind that rewired your nervous system, a sensation that could drive a person mad.

The Northern Lights dance, which I did not know until I saw them. They darted across the sky, blooming and unfurling in patterns that I could not detect, and it was a reminder of the ancient philosophers who believed souls must live in the sky because “the stars make us less lonely.” A garbled line from a Godspeed You Black Emperor song looped through my head as I watched: The sky’s on fire, and there’s no driver at the wheel—and it seemed impossible that we would waste our time down here arguing about money, imaginary borders, and local gods.

A road trip through the northwest peninsulas reminded me of my peculiar relationship with nature. I admire nature in relationship to the manmade—the park in the city, the lone stop sign in the desert—but landscapes without any place for the human overwhelm me in the Burkean sense of the sublime: a display of time and scale that I cannot absorb without feeling overwhelmed. Perhaps this reaction was exacerbated by reading Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, a summary of the inevitable trauma of climate change and how, just as the individual must reconcile himself to death, so must our species. And so many surreal vistas in Iceland amplified this sensation of living in end times, an effect further enhanced by a series of brutalist churches that looked as if they belonged to alien gods. With pools of boiling mud, sulfur coloring the air, green light streaking through the night, and columns of steam pouring into the sky, it was not difficult to imagine the need to invent gods and myths for an explanation.

When Abbot Suger walked into the Basilica of Saint Denis in 1144 and saw its Platonic geometries, stained glass, and pointed arches, he said, “It seems to me I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe.” This sentence came to mind often during my time in Iceland, and I hope the remainder of these photographs capture some of this.

Further Reading and Listening: Godspeed You Black Emperor, ‘The Dead Flag Blues’; Edmund Burke, The Sublime and Beautiful; Roy Scranton, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene; the Basilica of St. Denis.