Big Wheeling Creek Road runs through the hills of West Virginia and dips straight into the uncanny valley where a pair of thirty-foot gurus dance against the naked winter trees. Maybe it’s their bug-eyed grins, flowy arms, or brightly painted skin—something about these statues bothers the soul. They’re too lifelike. Too chipper. And they’ve deeply complicated my ideas about West Virginia.

There’s a massive gilded palace that looks like a postcard from a distant time and land. A life-sized plastic elephant sleeps in the parking lot. Gazebos surround a man-made pond where a sign warns about the possibility of violent swan attacks. Surveillance signs say Krishna is Watching. This is the campus of New Vrindaban, once the site of America’s largest Hare Krishna community.

Since its founding in 1966 in New York City, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness has become comic shorthand for the wild-eyed ideologue you endure in subway stations, airports, and crowded streets. Or rather, the ones who find you. The street preacher and proselytizer, the faith-dealers armed with trinkets, literature, and impossible questions. Do you know the truth? Have you been saved? Where will you spend eternity? But I cannot fault their enthusiasm. Given my excitement whenever I discover a new favorite book or song, I can only imagine my behavior if I thought I’d found some kind of god. If I ever peek behind the veil and see the secrets of the universe, I’ll probably want to tell people about it too.

The woman at the welcome center caught me off guard. I expected a hard sell for conversion. Instead, I felt as if I was signing in to see my dentist. “Feel free to wander around the grounds,” she said, offering a map. “When we built this place in the 1970s, we built it with love. If we needed a chandelier, we’d go to the library and read about how to build one, and we’d make the best chandelier you’d ever seen. It was beautiful because we worked for free. Because we worked with devotion. Not like today.” She gave a sweep of her hand as if gathering the broken pieces of a vision, a tiny gesture that somehow summed up the indignities of end-game capitalism.

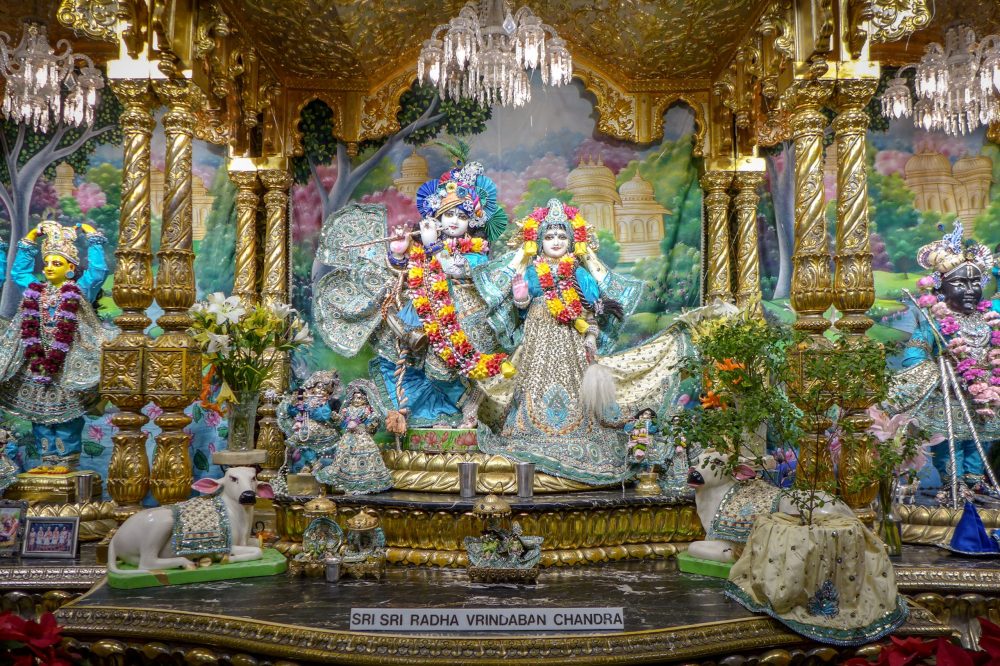

The temple was a vast polished floor beneath an ornate ceiling of carved teakwood. Black metal cages lined the walls, holding imprisoned gods and idols. A lion-headed Vishnu. Bug-eyed creatures, spangled saints, garlanded gurus, and yes, very beautiful chandeliers. All of this was monitored by a disturbingly lifelike recreation of the Hare Krishna founder, Swami Prabhupada. A gold watch glinted on his mannequin wrist.

Young faces with bright teeth fill New Vrindaban’s brochures, faces straight from central casting for one of those docudramas we know by heart by now: the idealistic American utopia that veers into something darker than the world it hoped to replace. A quick search of “New Vrindaban” is appended by words like scandal, abuse, and murder. A 1987 headline from the Chicago Tribune: “Murder, Abuse Charges Batter Serenity At Big Krishna Camp.” A year later in the Los Angeles Times: “Hare Krishna Swami in Prison for Killing Serves as Guru to Inmates.” Ten years later in The New York Times, 1998: “Hare Krishna Movement Details Past Abuse at Its Boarding Schools.” In the wake of two dead bodies and rumors of sexual abuse and drug trafficking, New Vrindaban’s guru faced charges of racketeering, mail fraud, and conspiracy to murder two ex-members who said he was abusing children. After hiring Alan Dershowitz as his defense attorney (see Mike Tyson and OJ Simpson), Kirtanananda Swami served two years of house arrest. A few weeks after his release, he was caught molesting a boy in the back of a Winnebago.

Yet another tale of people hungry for meaning falling prey to a charismatic predator who stripped his flock of their possessions and dignity. Moments of violence are happening right now in every corner of the world, but when these stories emerge from utopian communities, they feel far more damning: proof of a nagging suspicion that there’s no such thing as harmony in any society. That no matter how far-flung we travel or how spiritualized we become, the wickedness of men will find us. A line from Voltaire’s Candide comes to mind: “If hawks have always had the same character, why should you imagine that men have changed theirs?”

When it opened in 1979, Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold was heralded as America’s Taj Mahal. “A spiritual Disneyland,” the newspapers called it. As New Vrindaban’s membership and finances dwindled in the wake of the scandal, the palace fell into disrepair. The painted teakwood began to flake. The 22-carat gold leaf started to peel. But today the temple is back in fighting shape, part of an ongoing renovation funded in part by the community’s decision to lease its land for natural gas drilling. Returning to the car, I remembered the cynical little gesture of the woman at the welcome desk. Then the palace shrank in the rear-view mirror, vanishing behind a curve like something I had dreamed.

As I drove out of the hills toward the interstate, the Christian mega-churches, American flags, and billboards for faster download speeds, adult videos, and all-you-can-eat buffets seemed as spectral as America’s Taj Mahal, a collective hallucination like any other. I thought about our dogged faith in the fiction of nations and money and fame. All of it growing rickety, ready to be replaced by something new.