Flipping through an old notebook last night, I came across a page dedicated to the first time I saw a painting by Hubert Robert. Such beautiful cadence in that name: Hubert Robert. Say it out loud and you can’t help but smile.

I remember walking through a gallery at the Art Institute in Chicago, hurrying past portraits of the royal dead. Then I saw three massive paintings of ancient columns and arches stained with moss and time. The green-pink skies felt like the uneasy atmosphere just before a tornado. I nearly overlooked the tiny figures among the broken stones, their bodies dwarfed by architecture that had been designed for gods. A kerchiefed woman crouched over a puddle, scooping water into a pail. An elderly man groped among the rubble with a cane. A young man leaned against the shattered torso of a statue, flirting with two girls in bonnets. A mother cradled a bawling child. A floppy-eared dog gnawed a bone.

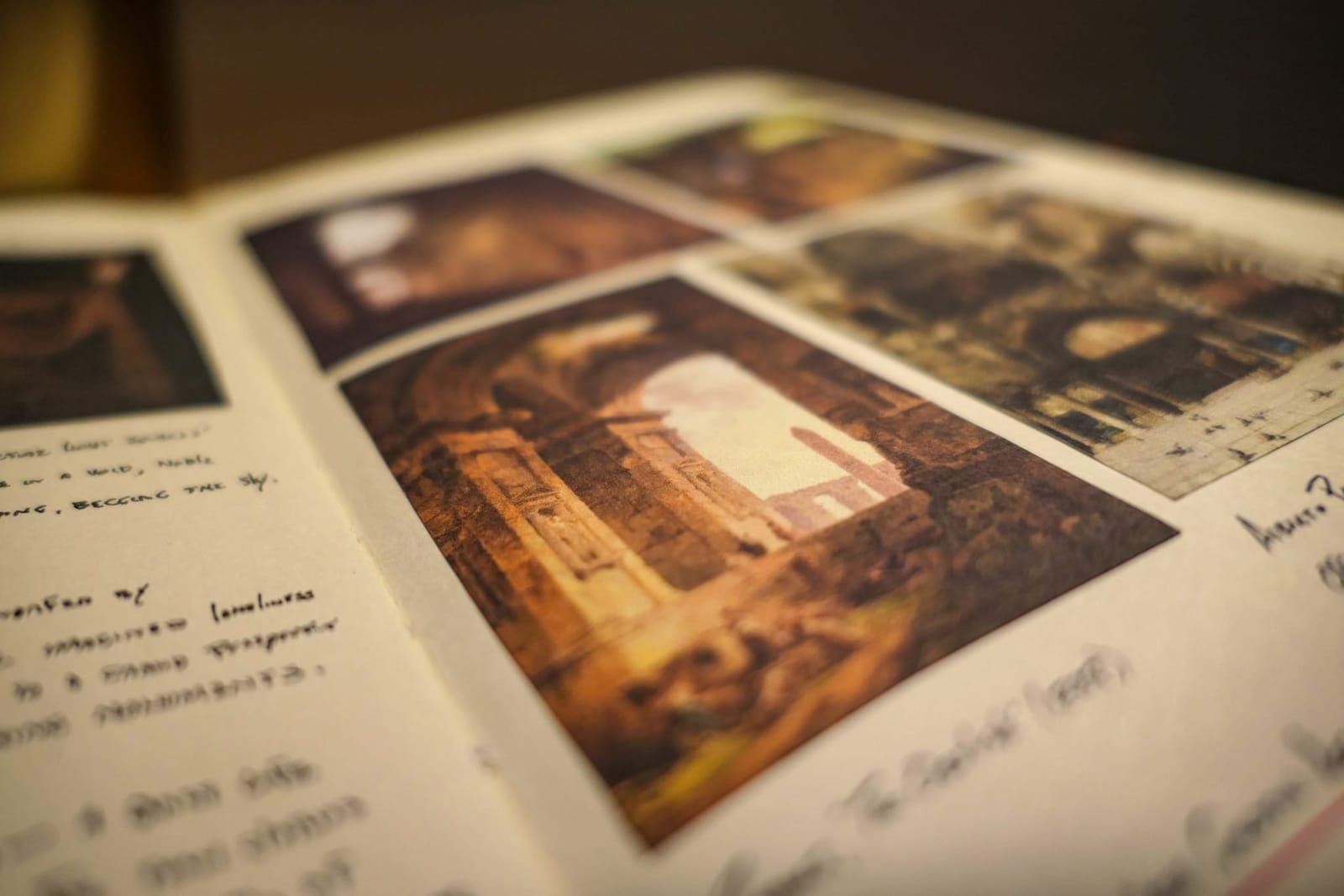

I studied these faces living among the ruins of a civilization that once belonged to giants. The label next to these paintings offered no information beyond the titles: The Old Temple, The Fountains, and The Obelisk—dispassionate names that gave them the force of fact or documentary. They were painted in 1788 by Robert, who was known for his capricci, a genre of architectural fantasy where scale and time are disregarded. He is now one of my favorite painters.

Standing before Robert’s ruins, I tried to understand the hum in my belly, the sense of longing. But it wasn’t that mysterious: everyone pines for a fictional past sometimes. Whether it is childhood or the romanticized splendor of Rome, nostalgia for a better time is hardwired. Preparing to tell the tale of Odysseus, Homer had said, “Come now, let me tell you stories of better men,” and the poet Ovid mourned the loss of the noble ages of gold and silver in the year 8.

The woman with her pail of water, the blind man, the flushed lovers: they were dwarfed by history, eking out an existence in its shadows. I wonder if Robert was mocking our desire to retreat into the past. Although his paintings are devoted to the relics of a grander age, they also feel like prophecy, a vision of future generations fetching water among the shattered cinderblocks of discount department stores. Such dystopian scenes once sparked a dark little thrill. But these days, the idea is no longer a remote entertainment or a weather report from a distant land.