Another frigid and atmospherically pointless day without any snow. The sun goes down at 5:27pm.

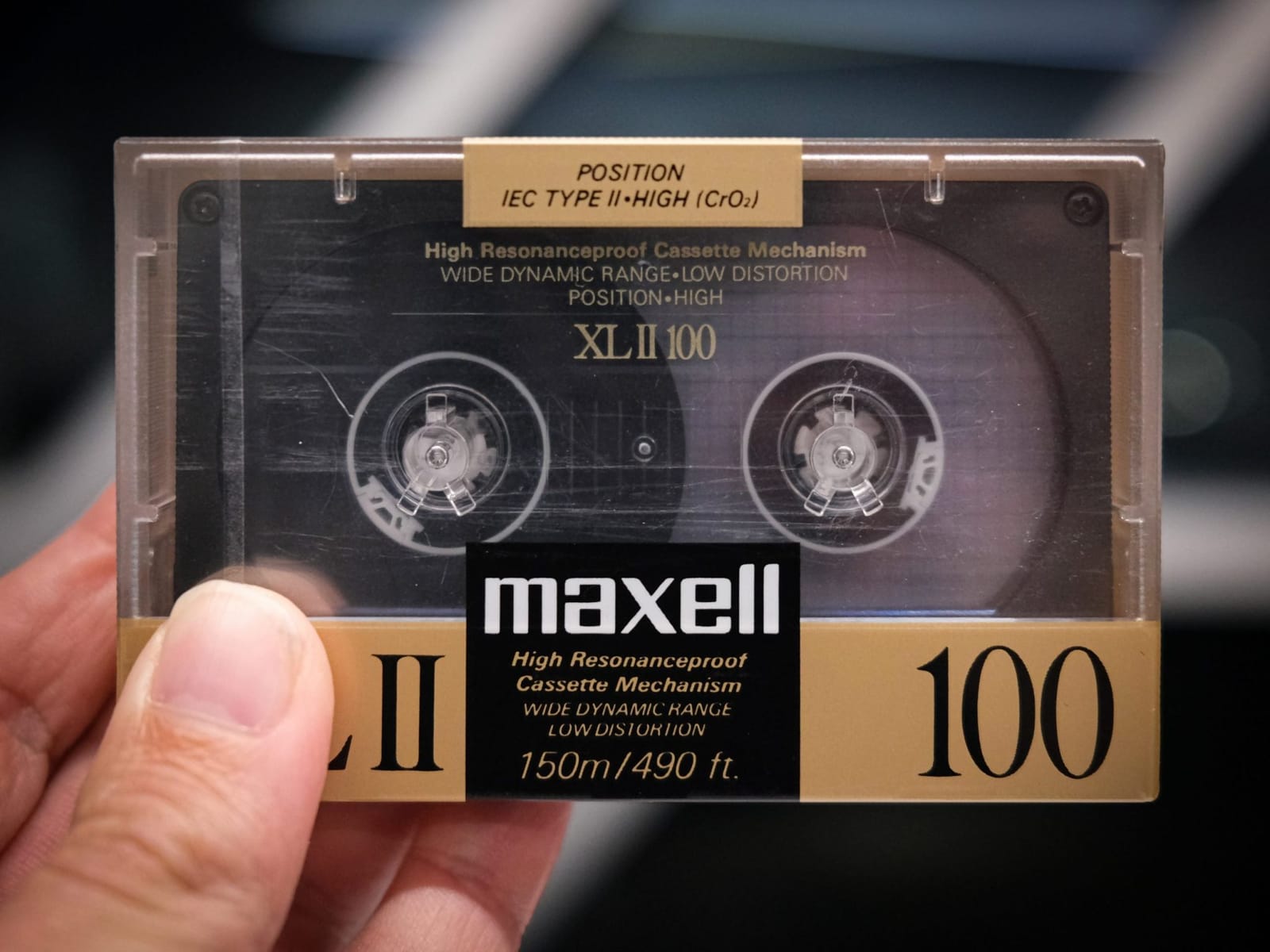

My brand new cassette tape arrived. It cost me seventeen dollars, but it was worth the money just to hold it. I haven’t held a cassette in years, and I found myself unwrapping it slowly, ritualistically, like a pack of cigarettes. As I peeled back the shrink-wrap, the effect was anticipatory, almost like returning to smoking: the familiar weight in the palm, the hum of possibility, of returning to better days.

It’s just a piece of plastic with a spool of magnetic tape, but it contains entire worlds. I remember solitary high school nights spent crouched over a Panasonic boombox in a metro Detroit apartment near Interstate 75, traffic hissing through the walls while my finger waited to release the pause button the moment the Electrifying Mojo played Kraftwerk or Cybotron again. You had to release that button just right for a clean segue between songs without any ugly clicks.

The reassuring kerchunk of buttons. The hum of machinery you could see. Punching out the plastic tabs on the top of the cassette if the recording was good. Or plugging them with paper if the tape was needed again. This was the tactile world of limitations, the parameters of a physical thing rather than a never-ending stream. Was my creative life any better then? Or is this just the nostalgia of a man settling into middle age?

I’m recording my little loops to cassettes because I crave the constraints of linear time. Maybe I simply want to return to a known way of being. There’s a fork in the road when it comes to reckoning with the 21st century: walk away from our increasingly humiliating and disorienting technologies, or make a cognitive leap and embrace the mess. But this is nothing new. In 1895, William Morris said, “Apart from the desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization.” Then came the Futurists and Constructivists and the rest of the Modernists. So much for that.