Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) opens with the disembodied heads of five children floating in the cosmos and gets weirder from there.

When we meet Robert Mitchum’s murderous preacher, he’s puttering along in a stolen car, talking to God. “Sometimes I wonder if you really understand,” he says. “Not that you mind the killing. Your book is full of killing. But there are things you do hate, Lord. Perfume-smellin’ things. Lacy things. Things with curly hair. There are too many of them. Can’t kill the world.”

This is a drive through America’s puritanical brainpan, a freaky portrait of the neurotic Christian obsession with sex, its hatred of women, and how dogma can be honed into violence. When Mitchum ogles a stripper, a switchblade erupts in his pocket.

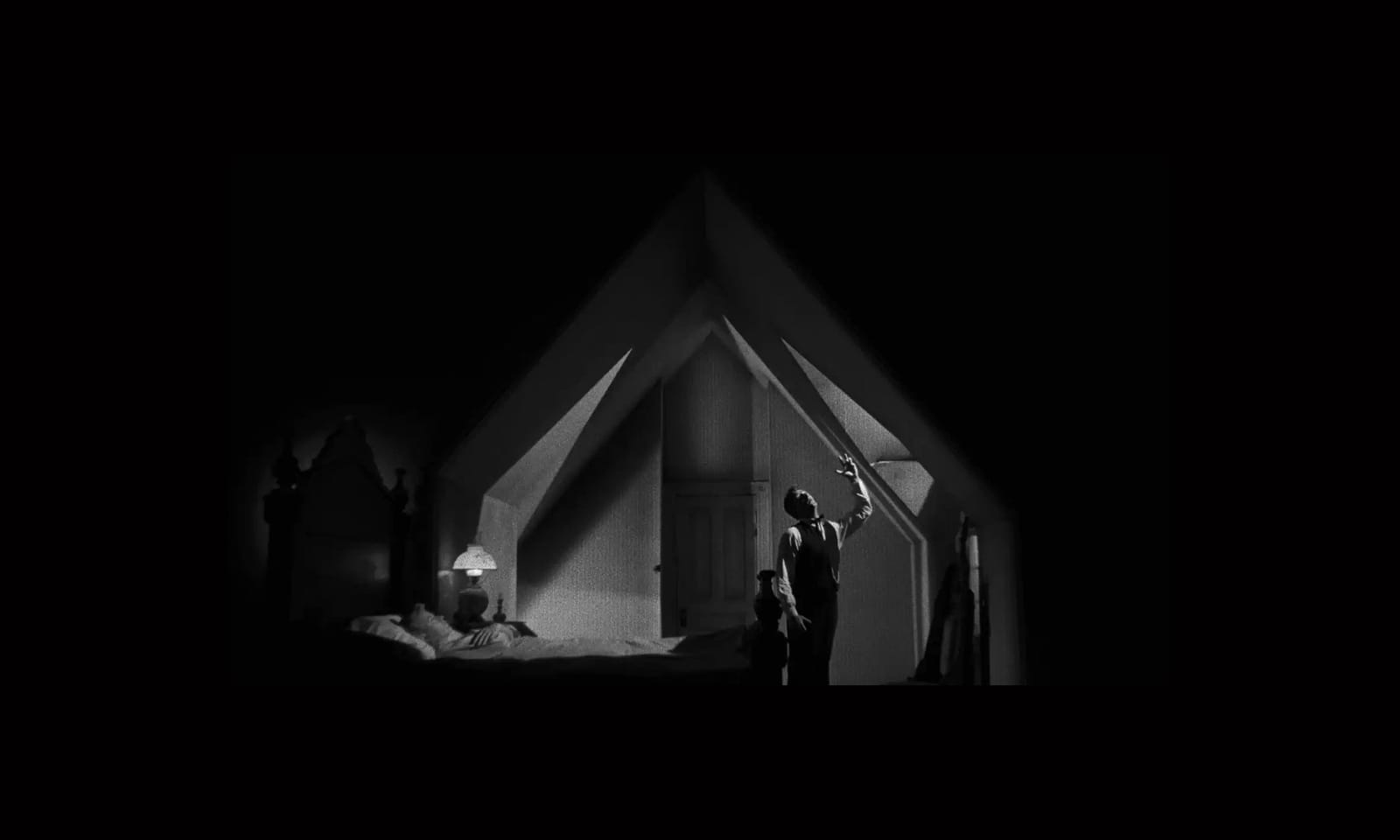

Then style enters the scene: the love/hate tattoos that inspired Radio Raheem’s four-finger rings; a bedroom that belongs in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari with its brute angles and unnatural light; midnight scenes along the river unfold beneath the stillborn skies of a soundstage; a woman’s watery grave looks like a snapshot from a dream.

As if skittish of the dark terrain it maps, the second half of the film retreats into a Scooby-Doo mood. Mitchum threatens precocious children and hunts down a rag-doll stuffed with cash, which becomes comic until Lilian Gish lays down the hammer between speeches about Moses and the Massacre of the Innocents. It’s a gothic sprawl of the sinister and the absurd, much of it soaked in Biblical verse punctuated by the occasional startling line: “And that slit in her throat, like she had an extra mouth.” This uneasy combination of the profane, the ridiculous, and the pious leaves The Night of the Hunter nattering at the mind—perhaps because we know faith can fuel all three conditions.