You have to really want to get to the island of Naoshima. A bullet train from Tokyo across five hundred miles in two hours. A sluggish taxi ride along a coastal road with five thousand stoplights. A ferry among the islands with muted freighters on the horizon, cutting through the fog.

Squid ink curry is my new favorite food.

Eliminating photography at museums is a righteous policy, although I was initially vexed by the need to take pictures to prove I had witnessed a piece of art. Nowadays, taking a picture is how we see an image or event, an amplified echo of Susan Sontag’s declaration in ’77 that “today everything exists to end in a photograph.” But this phantom twitch quickly faded as we moved through Tadao Ando’s severe concrete halls, and I was delighted to discover I was experiencing art with strangers in a way I hadn’t since the early 2000s. We weren’t ducking out of the way of each other’s shots. We lingered longer. Even the roomful of Monets held my interest.

But how to deal with a gigantic marble orb on a concrete staircase surrounded by dozens of golden three-pronged statues? To start, we moved around it slowly. We hunted for patterns and imagined the rituals that might occur in such a place. We lingered long enough that its strangeness became familiar, and soon we were dealing with it on its terms.

I enjoyed the ritual of removing my shoes before entering a gallery. It was somehow both formal and intimate. And quieter.

James Turrell's room of hyper-blue light gnawed at my peripheral vision until I was on the edge of a big-budget hallucination, unsure if he meant for me to be seeing what I was seeing.

We walked through a tiny silent town that smelled like a sauna. The wooden buildings were elegantly charred, and a sign above a shuttered door said Fortune Favors a Merry Home.

Fifty-two degrees is the threshold between a light and a heavy sweater.

For the first two nights, we dined next to a stern young couple who were always holding hands. The boy wore an oversized black coat, she floated within a billowy skirt, and I never saw them speak. They looked like they stepped out of an Aubrey Beardsley print, and I’m surprised how heartened I was to see that Romanticism is still kicking.

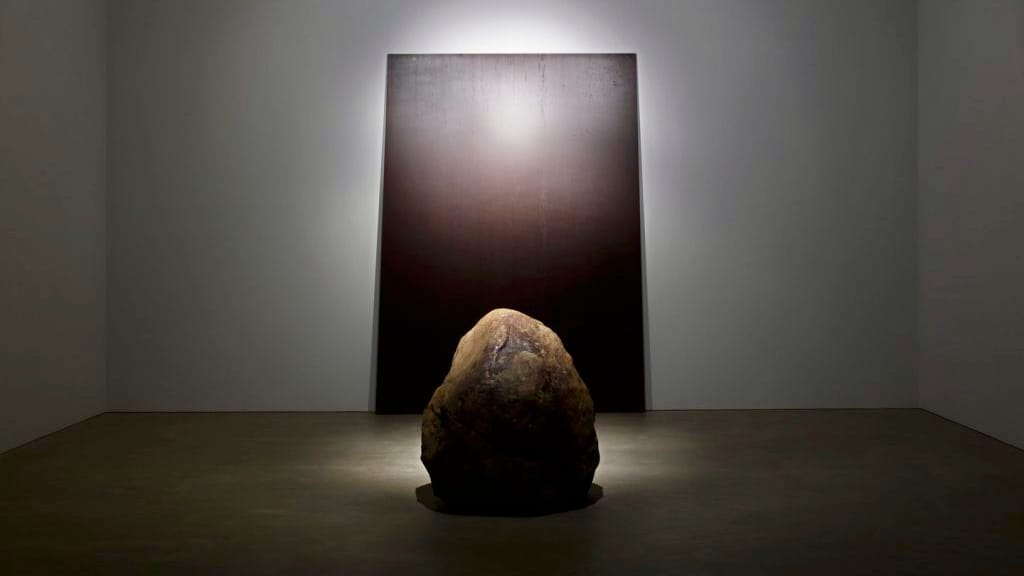

I was moved by a hunched boulder that appeared to pray before a glossy sheet of metal.

A line from Tatsuo Miyajima caught my attention: Keep changing. Connect with everything. Continue forever. I purchased a copy of his sketchbook, and C. bought a letter-opener shaped like a bird.

I always get drowsy on ferries. It’s such a fight to stay awake. The amniotic rocking of the waves, I guess.

Japan has the best coffee, especially the cans of iced black charcoal.

On the island of Teshima, we took a long rainy walk down an empty road to get our heartbeats archived for posterity at Christian Boltanski's Les Archives du Cœur, where a lone lightbulb in a dark hallway pulses to the beat of any one of the 90,000 archived heartbeats, generating the effect of a sinister rave in a forgotten factory.

You’re given two attempts to record your heartbeat. My first recording was a slow industrial thump that made me grateful for all the time I've spent running, but there was a slight scuffle against my shirt, so I tried again. The second recording was a disaster, and now the sound of a microphone snaking through a noisy forest of chest hair has been archived for eternity.

I believe the function of art is to create a situation where language falls apart, and this happened at Teshima. An absolute hush came upon me when I stepped into the strange curves of Ryue Nishizawa and Rei Naito's Matrix. Beneath the oval of a cloudy sky, droplets of water darted across the concrete to join larger rivulets that fed into a puddle. It's a remarkable feat to make water look alien.

But is there a correlation between the effort required to view a work of art and the degree of my appreciation for it? Perhaps this is why I've never felt anything close to the sublime while flicking through images on a screen.

Is a digital sublime possible?

In America, the men's restroom is typically a site of unconscionable body horror. But in Japan, even the public restroom at a far-flung bus station was immaculate. My home country is fucking barbaric.

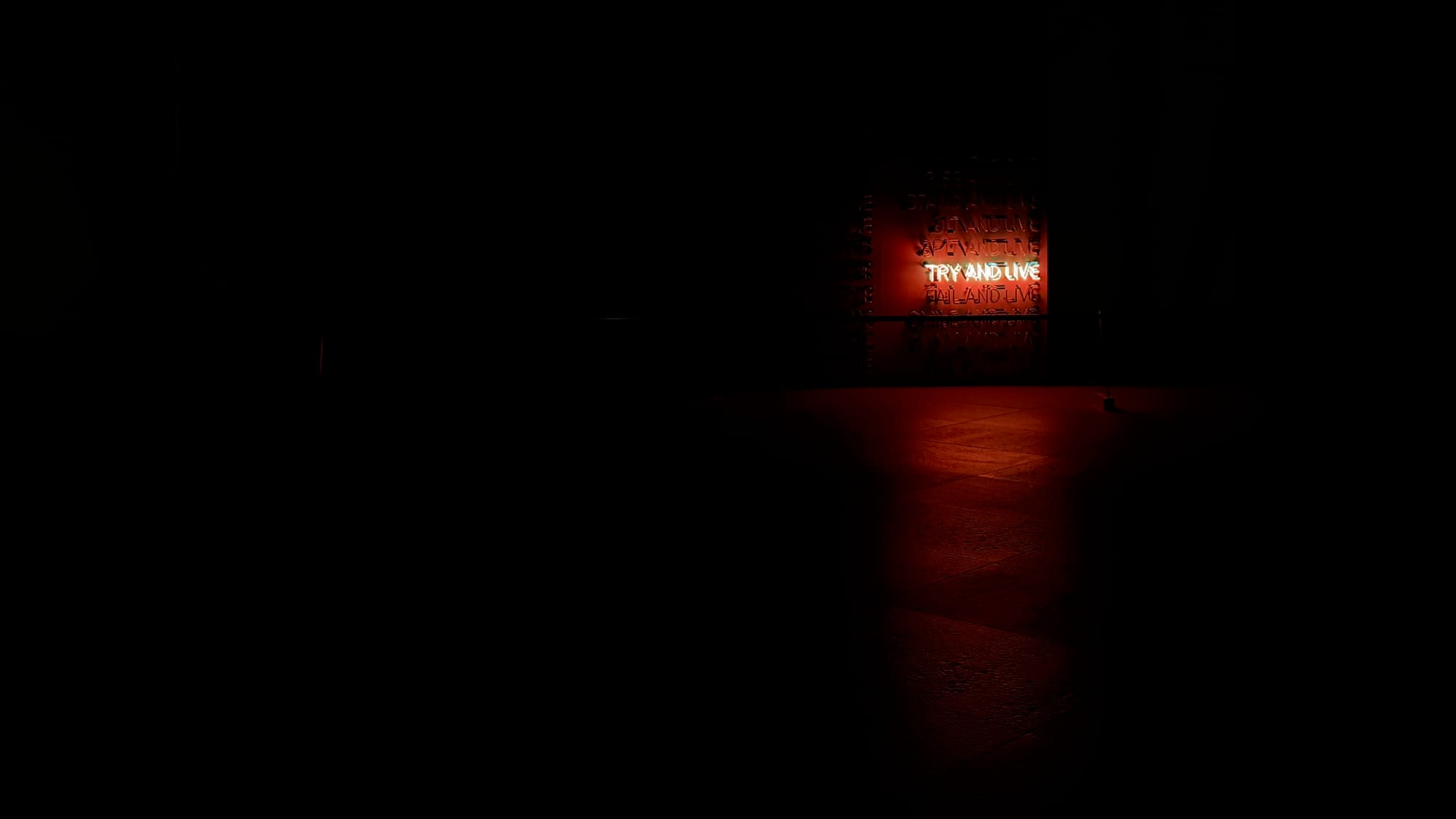

A resonant moment from Bruce Nauman’s One Hundred Live and Die says "Try and live."