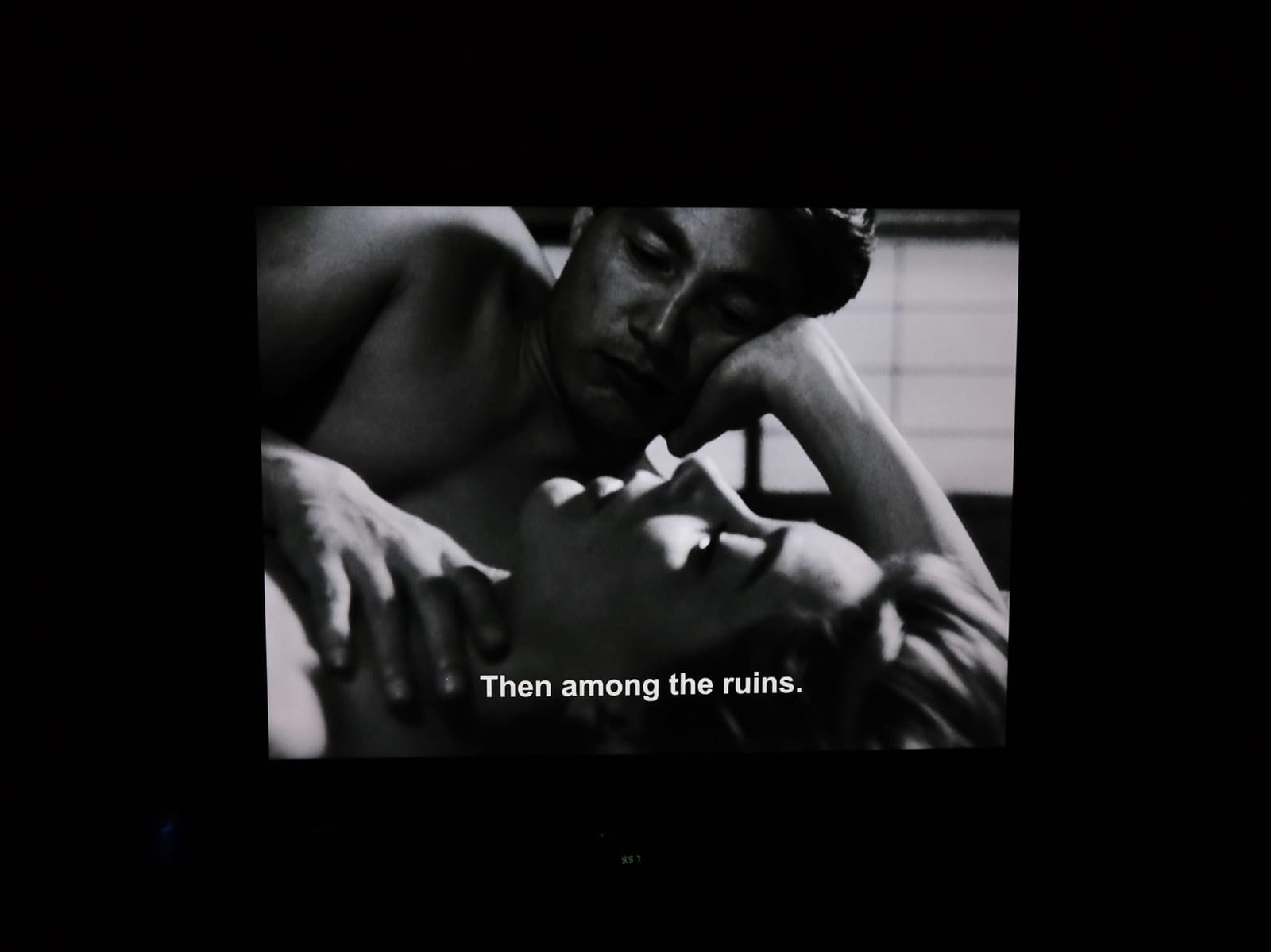

Last night I watched Hiroshima, Mon Amour, a film I hadn’t seen since my days in college. I remember it filling me with a particular and nameless kind of dread, and this mood has been on my mind lately: the overlapping of global calamity with the tragedies of our private lives. Released in 1959, Alain Resnais’s film is ground zero for French New Wave and perhaps the wellspring for most arthouse tropes. The camera lingers in dark rooms. Lovers speak in monologue and monotone. They thrash and sulk in shadows. They repeat themselves while gazing into the middle distance of the emotionally detached.

Much of the film is about recreating and relitigating the recent past. A French actress comes to Hiroshima to play a nurse in a movie about the atrocity of August 6, 1945—which occurred only fourteen years before. (Try to imagine, say, a film called 9/11, My Love released in 2015.) Her lover is a Japanese architect, and they discuss their private lives while surrounded by actors caked in makeup that resembles the burns from a nuclear blast. Tea rooms and cocktail lounges evoke bygone eras and far-flung locales, culminating in a tropical speakeasy called “Casablanca”. Along the way, the lovers move across tatami mats and stern Modernist lobbies, history collapsing as their desire to rekindle the first blush of youthful romance melds with the fallout from the bomb.

The French actress tries to attach herself to apocalyptic destruction, hoping to stave off indifference towards a new atomic age by narrating its horrors over a montage of destroyed bodies and post-blast footage. “You saw nothing in Hiroshima,” her Japanese lover repeatedly reminds her.

Hiroshima, Mon Amour is a profoundly fucked-up film that may not withstand the lights of 2022. But I can’t think of many movies that go after such big game by conflating the historical with the personal, the horrific with the romantic. It plumbs emotions unique to cinema, the ones beyond language or conscious thought—such as the dark urge to give our lives meaning by attaching ourselves to tragedy and violence, hoping to make an impression when we tell people we could have been the next victim, that we were just a few blocks away from the shooting or the blast site.