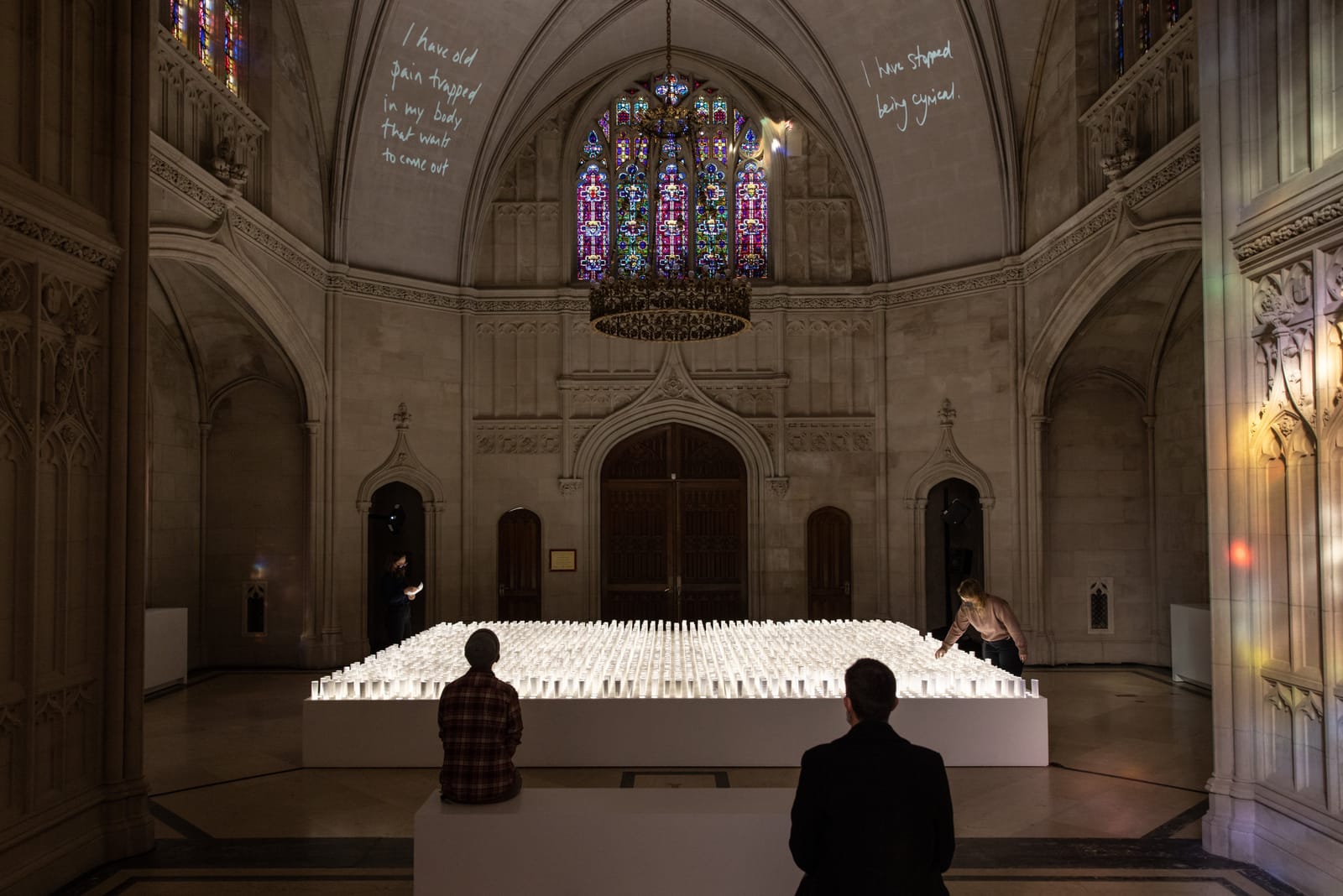

Displays of mourning and the contemplation of death were once critical components of public life, yet much of modern society has swept these elements from view. Today fewer people belong to a particular faith and many of us are left to confront death alone without the rituals and reassurances of community. How can our public spaces better address our relationship with grief, which is the most universal yet also most isolating of emotions?

Grief Is a Beast That Will Never Be Tamed is a mural that offers a meditation on loss and invites passersby to share rituals, beliefs, and texts which have provided solace. Inspired by the myth of the Minotaur, the first installation was created in Heraklion, Greece. The presentation of the mural included a discussion on grief and ritual with the community, and the project was also presented in Skagaströnd, Iceland, and Lisbon, Portugal.

A Meditation on Loss

Grief is a beast that will never be tamed, a creature born from broken promises and mistakes. We will always be together. I will never leave you. Everything will be okay. No matter how heartfelt these vows might be, one day they will collapse and leave us pacing the floors in shock, half-thinking we might enter a room to find the departed returned, sitting in a favorite chair. Instead we discover a new companion, a shadow in the corner.

Although experienced by everyone, grief remains fiercely private. Only we know the textures missing from our lives. The sound of a loved one’s feet padding down the hall, the heat and history pulsing beneath the way they said good morning—a voice never to be heard again. The shadow howls for answers. Infected by phrases like moving on and overcoming, we push this creature back into the darkness where it grows deformed, torturing us with dreams of running through unfamiliar rooms.

Our psyches are such elaborate labyrinths of defensive architecture, cluttered with alleys and walls that prevent grief from baring its teeth. But cracks always emerge. Grief might arrive on a gust of wind or a glimpse at a calendar, but it seems to prefer the night when silence allows it to be heard most clearly. Nails skitter across memories and regret burns like a fever. We try to fight but there is no battle here, no prize to be won. This creature cannot be buried or slain by a hero. One night it comes to you on its knees, asking for mercy, demanding to be seen. Perhaps grief cannot be tamed, but it can be loved.

Selected Responses

“I lost my mother to cancer on November 16, 2016. She was also diagnosed with Alzheimer’s a few years prior. I was aware the cancer was aggressive and our only recourse at the time was pain management. I was adamant to keep her home until she crossed over, and so I was there in our home holding her hand singing ‘Like my Mother Does’ when she took her last breath. It was the most excruciating and difficult thing I’ve ever had to do, but I wouldn’t have had it any other way. I wanted my mom to know I was there and she was not alone. Grief is an imaginary friend who follows me everywhere. Not always present to others, yet I know it is there. In every conversation, in every thing I do, the absence is always evident to me. I find doing things in her memory brings me purpose and comfort by continuing her legacy — so that everyone who meets me will also know her, my greatest inspiration and my hero.”

—Marie in Canada

“I lost a close friend and mentor, my fairy godmother. I was on the other side of the world when I got the call. The loss still feels raw and I often pretend that it isn’t real, that she’ll be there when I get back home. I wore heavy liquid eyeliner while in mourning; she always wore a full face with sixties sex-kitten eyes. Before I went away travelling, she gave me a $100 note with good luck messages written on it, saying it would help bring me home. I’ll never spend it. I’m making a performance piece about her, probably for closure, about the places we used to go. It is here that her absence is most palpable. Changing, becoming voids as well.”

—Anonymous in Skagaströnd, Iceland

“I lost my first born son to the needle just over a year ago — and yes, grief is a beast that will never be tamed. Feathers, he gives me feathers.”

—Anonymous in Melbourne, Australia

“My parents died when I was in my 20s. They died two years apart, both suddenly and painfully. I recently wrote a poem about them, which made me happy and grateful because they gave me the memories, guidelines, and values that I will carry with me for the rest of my life.”

—Carla in Lisbon, Portugal

“I have lost my sweetheart and my health. I keep trying to let go, but memories overwhelm me like an ocean crashing over me. Moments of tenderness from memories of loving and being loved help me treasure what was.”

—Nancy in Reno, USA

“I lost my mother one week ago. She suffered from cancer but died from bacterial meningitis. I feel sad but also very angry about her loss; I cry and I still have not realized that she’s gone. I feel angry about the injustice of losing good people who have so much to offer but for some reason they have to go. I must protect my father who lost his wife. My mother would talk about the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, the courage to change the things we can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

—Kostas in Heraklion, Greece

“I lost my mom on May 5 of 2015. After a long battle with cancer, she died in a hospice room. We watched her take her last breath. She seemed to fight the end — until it seemed her body reminded her there was no other way out. Grief feels heavy. It broke apart a family that, in my eyes, wasn’t entirely together. I try so hard to forgive others because she was so giving. This has proven to be very hard to do. Cancer and the cost of fighting it robbed her of the chance to retire in peace. I try to eat many of her favorite foods, recreate some of her favorite meals, wear her grey turtleneck sweater. Grief feels heavy and dark. I try to eat many of her favorite foods, recreate some of her favorite meals (perfect homemade flour tortillas elude me still), visit the library (she loved James Patterson novels), wear her grey turtleneck sweater, keep in touch with my sister and send her texts my mother might send, although she was terrible at texting. I kept the voicemail that she sent to me the week before she died. I spend time in the house she tried so hard to save.”

—Veronica in USA

“I’ve lost dear pets. I’ve lost my grandmother. But the grief that has stayed with me the longest is losing my father. We found out he had cancer in July and he was in the hospital every day until September. I became engaged less than a week after we found out, and I was married the year after. I bought a house. I was promoted at work. All big changes that he would have been so proud to see me accomplish. All moments that I would have loved to share with him. The grief still comes around, nudging me at times while I’m driving. Nudging me at times when I’m alone at home.I find solace when I react, do, or say things that remind me that I am indeed my father’s daughter. I am glad that I get to carry this with me, and I hope he is aware of the impression he made on me. He helped me become the strong and independent woman that I am today. I am part of his lasting mark on this earth. This keeps me going.”

—Maria in Connecticut, USA

“My partner just lost his aunt. She was like a mother and best friend to him. We’re in a different city so there has been lots of traveling before and after the death. As it only just happened, we are in shock and survival mode. Finding comfort is tricky. I guess it’s a mixture of trying to distract from the pain yet also finding moments for remembrance—very difficult in a world where you don’t get much time to reflect.”

—Mathew in Heraklion, Greece

“My wife died in the summer of 2011. Her last words to me were help me die. Not in an assisted suicide way, but rather to help her on her way. Her body was full of cancer and she was trying so hard to die that the adrenaline was keeping her body going. I spoke to her, encouraging her to relax and let go, to not fight it. After about twenty minutes she gently drew her last breath. I don’t remember most of the next two and a half years. Grief is still my constant companion. I don’t cry much anymore. I walk around with what I can only describe as emptiness. I enjoy many things today but the emptiness is still there lurking in the background. I was never angry about her death. The emptiness swallows the sadness, anger, and all the other feelings that could have resulted from her death. There is nothing to strike back at and alone at night is still difficult. Comfort is a funny word. There is nothing that comforts me. Friends help. I used to say that I hoped I would die first. After living through her death, I am glad I didn’t die first because she didn’t have to go through what I did. I’m old enough now to know that more of life is behind me than ahead of me and I hold fast in the belief that there is an afterlife and we will be reunited. In some way still unknown to me, we will be together again. I have learned not to fear death because I watched the grace and dignity with which she faced hers. This is my solace.”

—Fred in Maryland, USA

“I was at home in Iceland when my daughter rang me with the news that my son died in Australia. I am forever changed. I see my life as before and after the event; now there is a greyer lens on my existence. He was a musician and I listen to his voice whenever I need to.”

—Anonymous in Skagaströnd, Iceland

“Grief is something for which I am getting prepared. Due to the bad condition of a beloved person, I grieve for the moments I cannot share with her anymore, for the moments I cannot help but miss her. Sometimes I grieve for the person I have become without her, yet at the same time I feel blessed for the time she dedicated to me to become the person I am today.”

—Mika in Heraklion, Greece

“My uncle died by suicide. My mom told me on the way home from my dancing lesson, and I burrowed my head a little lower in my scarf and asked if there was anything to eat at home . . . to break the tension of my brothers standing around the table. He wasn’t in my life enough to really miss him, but I think I’m scared of what we might have in common. He was very intelligent but never had the chance to pursue academia in working class England in the 1950s, and I’ve dedicated my degree to him. I told him this at his grave.”

—Anonymous in Skagaströnd, Iceland