California was a shocking green as C. and I drove into Los Angeles, the hills almost alpine while we navigated ten lanes of bumper-to-bumper.

Last night we visited a friend in the Coachella Valley who studies water for a living. Water leads to fire, he said. The heavy rains that battered California last month are generating more grass which will die over the summer and provide more fuel for fires. We nodded quietly over our drinks, grateful for our yard of sand in Nevada.

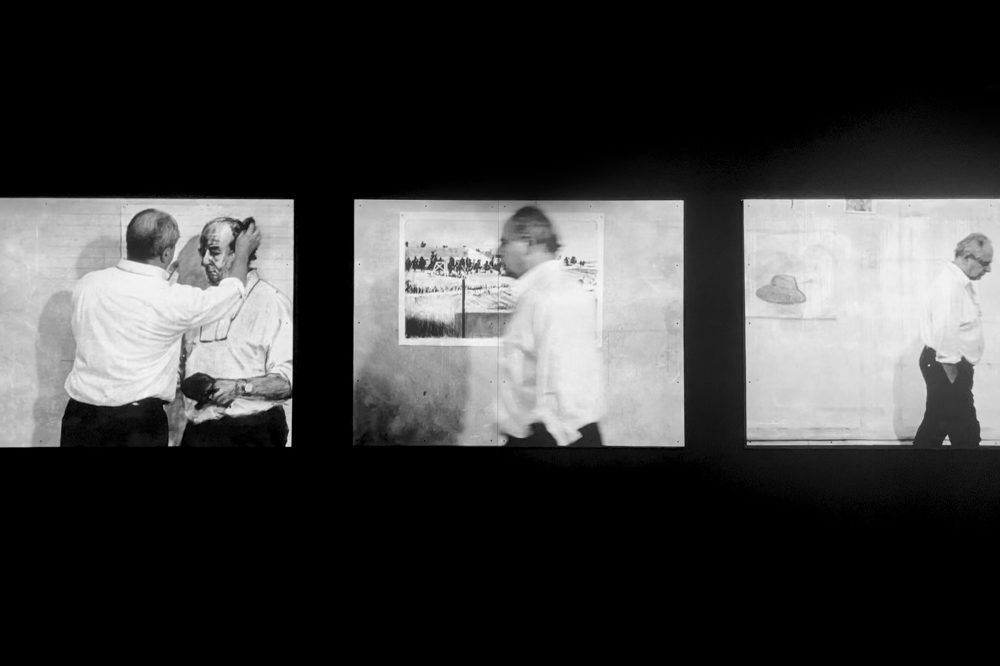

At the Broad Museum, we dug the William Kentridge exhibit, whose smoldering landscapes looked like scenes from a fast-approaching future.

Kentridge’s sketches and films meld the surreal with the political but, above all, they offer a reminder of the value of art as performance, a mode of play rather than a clinical intellectual exercise. The charcoal smudges, the streaks of erasure, the jittery handheld camera—at what point does imperfection accumulate into a distinct aesthetic? In Kentridge’s hands, the stray marks that my perfectionist brain would consider an error become a vital style, ripe with mystery and teeth.

Messiness will be a crucial tool in the footrace against artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile, a Chinese surveillance balloon was spotted over Montana. In our hotel room, C. and I caught a few minutes of the Pentagon’s press briefing, where a taciturn general studded with brass said the word balloon in every sentence. It was delightful. Can we shoot it down? asked the reporters. Where is the balloon now? “The public can look up in the sky and see where the balloon is,” the general said.

The Chinese spy balloon has become part of the weather report as it drifts across Kansas and Missouri. Perhaps this is a weird echo of the mood that swept America in 1957 when Russia launched Sputnik.